|

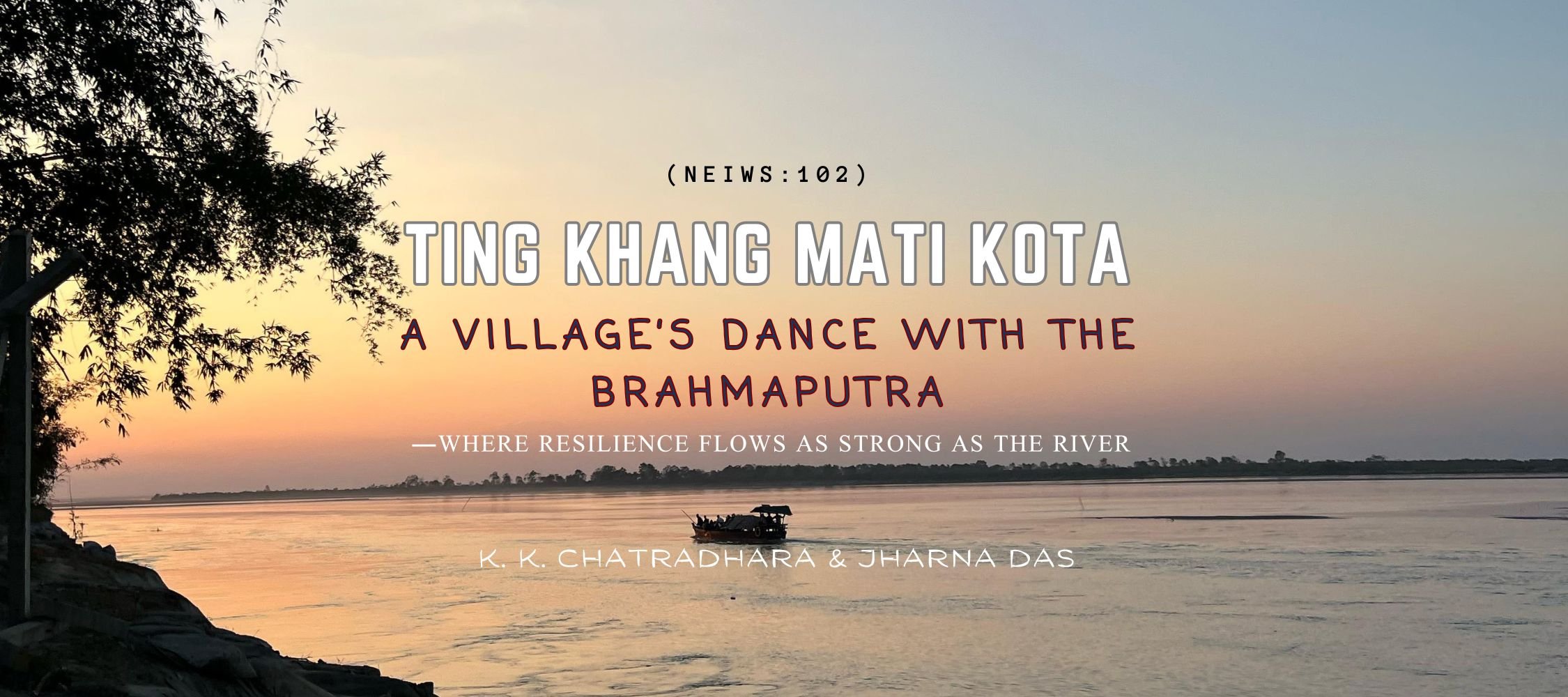

Ting Khang Mati Kota, a village settled on the south bank of the mighty Brahmaputra River in Assam’s Dibrugarh district, is a place where life is shaped by the ebb and flow of water. Located just northeast of the Bogibeel Bridge, it is part of the Tingkhong subdivision, a region known for its lush tea gardens, oil exploration, and vibrant agricultural activities. But for the people of Ting Khang Mati Kota, the river is both a giver and a taker—a source of sustenance and a relentless force of destruction. This village, like many others in the state, has a long relationship with the river—a relationship marked by both sustenance and devastation.

A Story of Resilience, Hope, and the Unyielding Spirit

Ting Khang Mati Kota is a story of resilience in the face of nature’s unpredictability. The village’s struggles with the Brahmaputra began in earnest in 1962, when a devastating flood coincided with the Indo-China War. This flood marked the beginning of a long and arduous battle against the river’s wrath.

The Floods of 1965: A Turning Point

The year 1965 was a turning point for the villagers. The river, swollen with monsoon rains, breached its banks and unleashed a devastating flood. The waters swept through the region, eroding farmland, destroying homes, and displacing over 100 families. Some families fled to nearby areas, while others sought shelter in places like Nagakhelia, Bhanga Ali, and Philobari. But amidst the chaos, a small group of 15 to 20 households decided to rebuild their lives in Ting Khang Mati Kota.

In 1972-73, the village was nearly abandoned as the land, covered in sand deposited by the river, was deemed uninhabitable. Most families moved away, but a few, including Prafulla Das, chose to stay. Determined to rebuild, they began farming again, cultivating paddy and vegetables like tomatoes and potatoes on the fertile land that the river had once nourished. For a time, it seemed as though the river had forgiven them, and paddy fields stretched across the landscape while their crops thrived. But nature had other plans—floods and erosion returned, washing away their hard-earned farmland and reminding them of the river’s unforgiving power.

In 1988, the villagers, with government support, built a ring dam to protect their land from the annual floods. For a time, it held. But by 1998, erosion began again, and by 2010, it had intensified, swallowing trees, farmland, and even roads. The concrete road built in 2018 offered some respite, but by 2024, the erosion had accelerated, threatening the very existence of the village.

The Cycle of Destruction and Rebuilding

The river, unpredictable and relentless, struck again. Floods and erosion returned, washing away the very land the villagers had worked so hard to cultivate. Each time, the people of Ting Khang Mati Kota picked up the pieces and started afresh. In 1988, they decided to take matters into their own hands. With the support of the government, they constructed a ring Bundh (round embankment)—a protective barrier against the river’s fury. For a while, it held. But time and the elements took their toll, and by 2024, the embankment was in disrepair, its condition precarious.

The year 2024 brought yet another flood, one that submerged the fields. The villagers, weary but determined, resumed farming as soon as the waters receded. They knew no other way of life.

A Village Divided

The river’s relentless erosion had not only taken land but also divided the village. Three distinct communities now stood where one once thrived. The proximity to the city of Dibrugarh offered some respite, as many villagers sought better opportunities there. Yet, despite their migration, the river remained a constant presence in their lives. The two chaparis—sandbars formed by the river—made the area particularly vulnerable to flooding.

Daily Life: A Rhythm Shaped by Water

Life in Ting Khang Mati Kota revolves around the river. At 4 a.m., the village stirs to life. Some head to the farmlands, while others tend to their kitchen gardens or go fishing. By 3 p.m., they collect fodder for their domestic animals. Evenings are spent in the Namghar, the community prayer hall, where villagers gather to pray and reflect. By 10 p.m., the village settles into silence, only to wake up the next day and repeat the cycle.

The women of Ting Khang Mati Kota are the backbone of the village’s resilience, strong and resourceful in the face of adversity. They work tirelessly in handlooms, weaving intricate patterns into fabrics, while also cultivating paddy and growing vegetables like tomatoes and potatoes. Among them are Anganwadi workers, nurses, and social workers, each contributing to the community in diverse and meaningful ways. The men, too, play their part, farming and fishing despite the constant threat of losing their land to the river’s relentless erosion. Together, they embody the spirit of perseverance and unity, driving the village’s cycle of recovery and hope.

The Bogibeel Bridge: A Double-Edged Sword

The Bogibeel Bridge, a symbol of modernity and connectivity, has brought both opportunities and challenges to Ting Khang Mati Kota. While it has improved access to nearby cities, it has also disrupted the river’s natural flow, exacerbating erosion. Near the village, two water channels shape the river’s course, their pointed edges directing the water in ways that have eroded the soil and deepened the riverbed.

The government’s attempts to control the river’s flow with geobags have largely failed, prompting the launch of a new ₹390 crore project involving IIT Guwahati to study and address the erosion. The plan focuses on deepening the river’s path to prevent water from accumulating and flowing back. However, the villagers remain skeptical. Having lived alongside the Brahmaputra for generations, they know its behaviour better than anyone and believe that without a thorough understanding of its patterns, any solution will be temporary at best. Their deep connection to the river has taught them that its power demands respect and sustainable, long-term strategies.

A Glimmer of Hope

Amidst the challenges, the village found glimmers of hope and progress, signaling a brighter future. The Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM), a transformative initiative, had successfully provided clean drinking water to the community, marking a small yet significant step toward improving the quality of life for its residents. This achievement not only addressed a basic necessity but also instilled a sense of optimism among the villagers.

The Shiva temple, a timeless symbol of faith and unity, continued to stand tall, serving as a reminder of the community's resilience and shared spirit. It was a place where people gathered, not just to pray, but to draw strength from one another in the face of adversity.

The people themselves were the heart of the village—resilient, resourceful, and unwavering in their determination to overcome the odds. Their ability to adapt and persevere was a testament to their strength of character.

In 2021, another significant change came to the village with the upgrade of the kacha rasta (dirt path) to a paver block road. This development brought immense relief to the villagers, especially since bicycles were their primary mode of transportation. The improved road made it easier for them to travel outside the village, access markets, and connect with neighboring communities. It was a tangible improvement that symbolized progress and the possibility of a better future.

A team of researchers from IIT arrived in the village, commissioned to study the flooding problem. They walked along the embankments, spoke with the villagers, and mapped the river’s history. Their findings would shape the future of Ting Khang Mati Kota, offering a glimmer of hope for a more sustainable solution.

Together, these changes—clean water, a renewed road, and the enduring spirit of the people—painted a picture of hope and resilience, proving that even in the face of challenges, progress was possible.

A Community’s Strength: Living with the River

What sets Ting Khang Mati Kota apart is the resilience and resourcefulness of its people. Despite the constant threat of erosion, they have adapted to life on the river’s edge. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when cities struggled with resource management, the villagers of Ting Khang Mati Kota relied on their own resources to survive. They fished, farmed, and supported one another, proving the strength of their community.

Yet, the fear of erosion looms large. The villagers love the river, but they are terrified of its power. They have seen their land disappear, their homes washed away, and their livelihoods threatened. But they continue to fight, to rebuild, and to hope for a better future.

A Call for Understanding and Action

The story of Ting Khang Mati Kota is a call to action. It highlights the need for sustainable solutions that respect the river’s nature and the wisdom of the people who live alongside it. The villagers’ traditional knowledge, passed down through generations, is a valuable resource that should not be ignored. As the government and experts work to address the erosion, they must involve the community, listen to their experiences, and learn from their resilience.

For now, the people of Ting Khang Mati Kota continue to live with the river, embracing its gifts and enduring its challenges. Their story is one of strength, adaptability, and an unbreakable bond with the land they call home. As the Brahmaputra flows on, so too does the spirit of Ting Khang Mati Kota, a testament to the enduring power of community and hope.

Historical Timeline: A Village’s Journey

- 1962: The Indo-China War and the devastating flood of 1962 mark the beginning of the village’s struggles with the river.

- 1965: Over 100 families are displaced by floods, relocating to Nagakhelia, Bhanga Ali, and Philobari.

- 1972-73: The village is nearly abandoned due to sand deposits. Only a few households, including Prafulla Das, remain.

- 1985: Formation of the Naba Jagaran Samiti, a community organization.

- 1986: The play Sati Radhika is performed, reflecting the village’s cultural resilience.

- 1988: Construction of the ring bundh to protect against annual floods.

- 1998: Erosion begins again, threatening the village.

- 2006: A road is constructed, offering some connectivity.

- 2010: Erosion intensifies, washing away trees and farmland.

- 2018: The road is concretized, providing temporary relief.

- 2020: The COVID-19 pandemic tests the village’s resilience, but they survive on their own resources.

- 2024: Erosion accelerates, posing an existential threat to the village.

Conclusion: A Future Anchored in Hope

Ting Khang Mati Kota’s story is one of survival, adaptation, and hope. The river, both a giver and a taker, has shaped the village’s past and present. As the people of Ting Khang Mati Kota look to the future, they do so with the knowledge that their strength lies in their community and their connection to the land. The river may be relentless, but so too is the spirit of Ting Khang Mati Kota.

Reflections on a Transformative Experience: A Young Researcher's Journey to Ting Khang Mati Kota

As part of the 2024 Water Training Program at Dibrugarh University, I had the privilege of embarking on a life-changing visit to Ting Khang Mati Kota. This experience was more than just a field study; it was a journey of discovery, growth, and profound understanding.

Witnessing the harsh reality of flooding firsthand, I was struck by the resilience and strength of the human spirit. The villagers' struggles, stories, and unwavering determination left an indelible mark on my perspective. Standing on the river's embankment, gazing at the mighty Brahmaputra, I felt a deep sense of responsibility. The river's power and majesty demanded respect, nuanced understanding, and sustainable solutions.

This experience underscored the importance of community-led initiatives, shared knowledge, and collaborative approaches. The people of Ting Khang Mati Kota have learned valuable lessons through decades of hardship, and it is our responsibility as researchers, policymakers, and global citizens to carry their story forward.

I extend my heartfelt gratitude to the villagers, particularly Ekalavya Prasad, K. K. Chatradhara, and Monuj Dutta, who guided me through this transformative journey. Their kindness, wisdom, and unwavering spirit have left a lasting impression, reminding me of the power of community and shared knowledge.

As I reflect on this experience, I am reminded that the story of Ting Khang Mati Kota is far from over. It is a testament to the unbreakable bond between people and the land they call home. The river continues to flow, carrying with it the hopes and dreams of a community determined to thrive against all odds.

A Note from a Villager

By Jharna Das

To be born and brought up in a village close to the mighty Brahmaputra has always been a source of immense pride for me. The river is not just a body of water; it is the lifeline of our village, shaping our lives in ways both visible and unseen. Growing up in a noi poriya gaon—a village by the river—my connection to the Brahmaputra is as natural as its flow.

My childhood was deeply intertwined with the river. On weekends, my parents would take us to the riverbank, where we spent hours playing in the water, washing our shoes and socks after school, and even scrubbing down our bicycles. These small but significant rituals brought us closer to the river, making it an integral part of our daily existence. Evenings were magical, with boat rides alongside my father, visits to the chaporis—the river islands—for fresh vegetables, and the routine of sending our cattle to graze near the river before bringing them back home. The Brahmaputra was more than just a waterway; it was a friend, a provider, and a constant presence in our lives.

For many in our village, the river is a source of livelihood. Fishing is an age-old tradition, passed down through generations, sustaining numerous families. The fertile land near the river, especially on the chaporis, allows agriculture to flourish, while our livestock depend on the grasslands the river leaves behind. The knowledge of fishing, farming, and coexisting with the river has been inherited over generations, making us deeply connected to our land. The river has always given generously, and we, in return, have learned to respect its power.

But just as the Brahmaputra provides, it also takes away. Every monsoon, the water levels rise, and with it comes the fear of floods. Erosion is a cruel reality, slowly claiming agricultural land and homes, inch by inch. The embankments meant to protect us stand as fragile barriers against the river’s might. Over the years, the loss of land has deeply impacted our way of life. Once-thriving farmlands have shrunk, forcing many farmers to give up agriculture altogether. Fishing, too, has suffered, as the changing course of the river and the unpredictable floods have reduced fish populations. Many families who once depended on the river for sustenance have had to find alternative means of earning a livelihood, moving to towns and cities in search of work. The river that once nourished us now challenges our very survival, making adaptation the only way forward.

Yet, we have always trusted the river, believing that it gives and takes in equal measure. However, the year 2024 was different. The erosion was unlike anything we had seen before—faster, more destructive, swallowing entire chaporis and bringing the river dangerously close to the embankments. Fear gripped the village as people watched helplessly, knowing that the land they stood on might not be there tomorrow.

As part of the 2024 Water Training Program at Dibrugarh University, I had the opportunity to return to my village with a new perspective. This visit was more than an academic endeavour; it was a deeply personal journey, a chance to see my home through new eyes. Watching my fellow trainees witness the reality of floods, the struggles of my people, and the undying trust they place in the river made me realize the depth of our resilience. Families who had lost their lands still found ways to rebuild, fishermen continued to set sail every morning despite the unpredictable waters, and farmers planted their crops with faith, knowing that the river, despite its wrath, was still their greatest ally.

The Brahmaputra continues to flow, carrying with it the stories, struggles, and dreams of our people. It is a force that demands respect, patience, and adaptation. It nurtures and destroys, challenges and provides, but above all, it teaches us the value of perseverance. Every time I leave my village, I take with me the memories of golden sunsets over the river, the scent of rain-soaked earth, the sound of waves crashing against the embankment, and the resilience of my people. No matter where I go, my heart always longs for home—the land where the river flows, shaping the destiny of those who call its banks their own.

Key Takeaways:

- Community-led initiatives: The importance of community-led initiatives and shared knowledge in addressing the challenges posed by the Brahmaputra River.

- Collaborative approaches: The need for collaborative approaches involving researchers, policymakers, and local communities in developing sustainable solutions.

- Resilience and adaptability: The remarkable resilience and adaptability of the people of Ting Khang Mati Kota in the face of adversity.

- Sustainable solutions: The importance of developing sustainable solutions that respect the river's power and majesty, while addressing the needs and concerns of local communities.

Recommendations:

- Support community-led initiatives: Provide support and resources to community-led initiatives and shared knowledge platforms.

- Foster collaborative approaches: Encourage collaborative approaches involving researchers, policymakers, and local communities in developing sustainable solutions.

- Promote resilience and adaptability: Support initiatives that promote resilience and adaptability in the face of adversity.

- Develop sustainable solutions: Develop sustainable solutions that respect the river's power and majesty, while addressing the needs and concerns of local communities.

(This article is written by K. K. Chatradhara, based on a field visit as part of the 2024 Water Training Program at Dibrugarh University, organised by CSWS-DU in collaboration with NEIWT, NEADS, and supported by Henrich Böll Stiftung, New Delhi Regional Office.)

Geolocation is 27.454971, 94.854371