|

Let’s go!

The idea cropped up from nowhere!

We were thinking of visiting one of the villages that was ravaged by recurring deluge and erosion, and document the resilience dwelling on the edge of a river and their traditional knowledge of coping with misery and uncertainty.

The word, Mudoibeel, generally evokes images of a vast water body or wetland. No one knows the ecological past of the area, which has now come up as a village close to the river Subansiri.

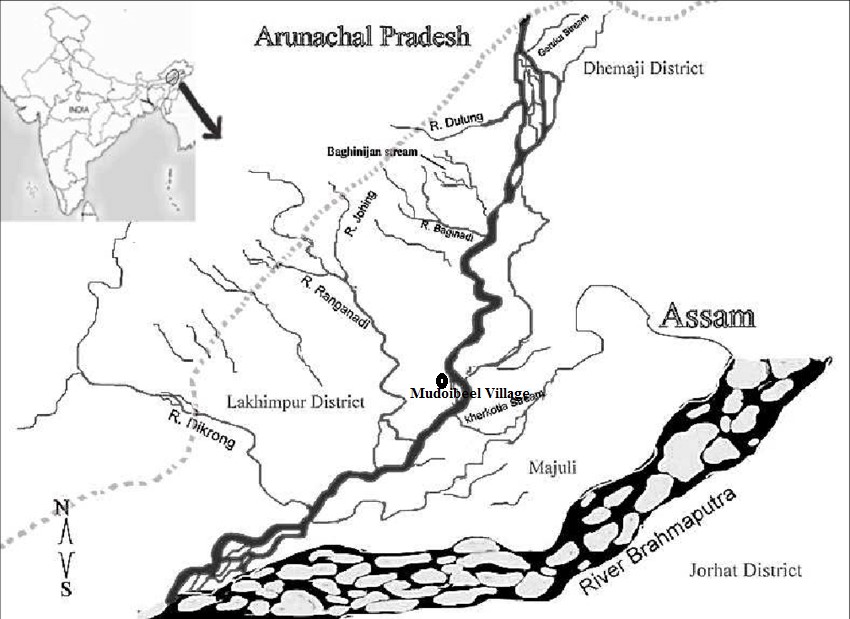

For decades, the flood-plains dwelling villages, especially on the north bank of the mighty Brahmaputra in the upper Assam district of North Lakhimpur, have been facing the wrath of its two major tributaries –Subansiri and Ranganadi. Both the rivers originate from the uplands of Arunachal Pradesh and flow down south across the North Lakhimpur district, and join the northern flank of the Brahmaputra. Subansiri, which emerges from the glacial height of the Tibetan plateau, is the largest tributary on its north bank. At the same time, the Ranganadi comes out from the catchment hills of Arunachal Pradesh.

Life-threatening annual floods and the loss of land caused by river bank erosion are the two perennial features of the flood plains, and their fragile ecosystem represents this tragedy.

The technological interventions for addressing these complex problems, such as constructing large dams and barriers to harness the mountain waters, have not yielded any durable solutions; on the contrary, these engineering ‘solutions’ are found to be utterly inadequate, and a living example of ecological disaster. The Ranganadi hydropower project, developed by the North Eastern Electric Power Corporation (NEEPCO) and commissioned in 2002, is one such controversial development scheme, which has turned out to be the cause of countless miseries for the river basin population. No matter what the flood control measures are, the river invokes its right over the flood plains. The embankment built alongside worked only as a sluice gate; if breached, the gushing waters would wash away everything downstream. And that has been a recurrent event in the area.

The trail to Mudoibeel

In the early week of March, just before the nationwide lockdown was announced in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, when we embarked on our first water talks, Mudoibeel, we thought, would be an ideal place to explore!

Located on a bend of the river Subansiri, Mudoibeel village is a part of the Panigaon gaon panchayat (GP) under the Telahi block in the North Lakhimpur district. Two more villages bear the same name: 1 No. Mudoibeel and 2 No. Mudoibeel, but they fall under the Lohit Khabolu GP. Our destination was one of such villages where people did not have a permanent address. They are always on the move – they live at the mercy of the river!

We took the Kamalabari (KB) road from the North Lakhimpur town, crossed Panigaon Chariali, and drove about 24 km towards the south until we reached the RangatijanTiniali, a tri-junction. At this tri-junction, we asked for the direction to Mudoibeel; we were led towards a narrow, rough stretch of road – nay, it’s an embankment. As we drove along, children, who were playing around, hurriedly moved aside; a flock of chicken and ducks and a few piglets scurried past. This embankment seems to be the only space of recreation for the local people, and a foraging ground for domestic animals. A network of embankments crisscrosses the area and their heights seem to go up year by year, while the farmlands below continue to be exposed to the backlash of trapped water.

We drove to a distance where the river emerged before us. A ferry to Majuli waits at the Khabalu ghat for passengers and goods – potatoes, lentils, kerosene, and stuff like that. The destination may change, depending on the passengers and the local cargo. We passed by the vast expanse of paddy fields and wild grasses.

Finally, we reached a place where some of the villagers were waiting for us, near a newly built high-rise platform. The Indo Global Social Service Society, a regional NGO, constructed this raised platform for the villagers to take shelter during the flood. The river took a slight bend here, on the eastern side of Mudoibeel. The air was cold and dry. The landmass, made of white sand deposits, looked sterile. The water was cold, flavoured by melting snow but somewhat muddy. On the other side of the river, a patch of forgotten land was now covered by wild bushes.

We, along with the villagers, decided to take a walk through Mudoibeel. We saw that a few fishermen harboured their canoes and tethered them with a worn-out rope. The riverside is an exhibition of their association with the river. Scattered logs carried by the river and stranded boats; shells and bones; and remains of bamboo artifacts that were once a fishing instrument; or a bright piece of red polyester cloth all lying around the river bank – this is how life tethered to the river.

Two little girls showed up. They had keelings (ki’ling- meaning a water vessel in Mising dialect), silver vessels tucked by their waist, held with usual fluidity like holding their younger siblings. Stained are the pots with rust colour due to high iron content in water.

Villagers seemed entirely unaware of the importance of clean and safe drinking water. A school teacher of Mudoibeel once tried to get the water that the villagers drink tested; he had sent a sample for testing to the public health laboratory. The lab report confirmed the presence of contaminants in the water. But the issue rested there. No action, no awareness campaigns, no water treatment facility from the public health authority came up.

Some village women crossed the location. They were wearing colourful patterns. The usual way, they would pass this emptiness of the high sun. It was past noon, and it was their turn to fetch water for the rest of the day. Having done all the morning chores, some women went out for fishing. The two girls prepared for a bath, so we passed by them.

A machine boat was passing by, roaring through the water and belching out black smoke. These boats operate from Khabalu ghat to other banks, to Majuli, Kherkata, and other places, carrying both passengers and essential goods. The contrast looked dull with the bright noon sun.

Walking along the river bank on the edge of Mudoibeel, we got a fair glimpse of village life. The centre of the village is about half a kilometre from the river. A giant banyan tree, adorned with bells and red cloths wrapped around it, and cheap incense sticks and sticky oil lamps lay scattered on the ground, stands with sublime pride.

The school was closed – often too early, the villagers informed us. The routine of the school has never been followed. The teachers follow the same non-existent road network; reach school late, attend a class or two, and then it’s time to leave for home. The education department has never done any monitoring. The villagers, too, lack interest in running the school as it should be. Lack of participation from their part and disinterested approach of the teachers perpetuate criminal neglect of children’s education and learning. The entitlement and the right to quality education get buried only in official documents and not visible in academic practices.

As we sat down to reflect on our conversation on water, a barrage of other issues converged. How could this village be called anything like ‘Mudoibeel’? We asked. One elder offered his version of the local history. ‘Mudoi’ is a wandering tradesman on a boat; ‘beel’ is a water body, like a wetland or a lake. The current landscape defies the explanation offered by the village elder. There are no wetlands around the village, though some local traders frequent the ferry ghat to and fro with their wares, including local produce. Has anything been erased from its history? Did some ‘Mudoi,’ a legend or a popular hero in folk stories, come here to trade? Do we have a document buried somewhere to delve deep and look back?

‘Mythical’ History of Mudoibeel

“We are only a part of its history,” American Doley, a village elder, retorted. “We came here in 1952 from our ancestral village, Dafala Pather near Kherkata, then under Majuli sub-division in Jorhat district, about 30-35 km south of Mudoibeel.” Kherkata became part of Majuli when it was upgraded to a district. Doley claimed that his ancestors travelled by boat to Mudoibeel, a wetland and common fishing ground. There was a booming trade in dry fish; the dry-fish market continued till 1995. Traders would come and procure stocks that they would transport chiefly to Jagiroad, one of the largest dry fish markets in Asia, about 350 km from the village. As time passed by, this wetland disappeared into the heart of the Subansiri. The river has eroded a vast chunk of land, about 3-4 km, in the last three decades.

He also narrated a legend that is associated with one mythical king, Arimatta, who, it is said, had dug a few ponds around the village, which is now believed to be covered in sludge and marsh. Revered are these ponds, and no one dares to step in; these swamps are the abode of a supernatural spirit Kalika. Villages showed us a few spots surrounded by deep, dense forest and clusters of bamboo groves. Walking through the jungle path, one indeed gets an eerie feeling! The story of Arimatta, king of the early-medieval Assam, was as amusing for us as the tall claims made by the villagers were confusing. We do not know if any chronicler has ever documented the presence of these medieval features. But we thought it was better to leave the myth alive without questioning the integrity of their belief. Many historically unverified and mythically linked water bodies in and around the location have disappeared, either by sand casting or erosion.

Ecological impact– the link between River health & Human health

Impermanency is one of the critical features in erosion prone areas – there is nothing sure about life and living conditions. Therefore, villagers generally do not invest in proper housing and other lasting infrastructure. It’s pretty evident in villages settled across the flood plains. The communities such as the Misings build their houses on bamboo stilts to allow normal floodwater flow beneath the house. And when the floodwater level rises, they move to a nearby higher concrete platform built for temporary shelter for the affected people.

“We are Misings, and we live in stilt (elevated) houses traditionally. We don’t fear floods or a mad river as time has taught us to live and celebrate with it,” Mithun Doley, an unemployed graduate, told us. “But the problem is with erosion. Our farmland, our houses, everything depends on the mercy of the river,” he added. Erosion compels people to move and find a new home again. “We have changed our houses a countless number of times,” Doley said. In 2000, they left the old settlement and came to the present location, fondly renaming the newfound village as 1 No.Mudoibeel.

Traditional knowledge for Riverbank protection

Villagers said, in the past they protected certain tree species, especially ‘Karak’ trees, as they were locally known, which naturally grew along the riverbank and almost everywhere in Mudoibeel. Karak trees have a dense network of interconnected roots that tightly hold the soil; it was a kind of mangrove vegetation that protected land from erosion and provided sanctuary to certain native fish species like Cheng (Channa Orientalis) breeding. Unfortunately, people failed to recognise the excellent ecological function of the native Karak forest. They began to cut them down as trees because these were good as firewood, too. Over the years, the entire Karak forest disappeared due to unregulated felling of these trees for profit. Only a few of them survived, villagers said. There is a village called Karakani (where Karak grows) a few kilometres downstream along the river, which also faces the same problem of erosion now.

How do the people of Mudoibeel manage water, particularly for drinking? Usually, the villagers use river water for their household needs; they filter the water with basic materials like sand, pebbles, and charcoal for drinking. Most of the villagers drink filtered water; some also boil the filtered water before drinking. It seems fine during regular days, but problems crop up during floods when water gets muddy and polluted. The women face all the brunt of water woes, as they are directly involved in collecting and storing water for meeting household needs. But none of the women in Mudoibeel spoke anything about water when we discussed it. They just quietly sat and listened to the conversation. Their sun-burnt skin, the yellow pigment of their eyes, and rough hands exhibit the severity of daily struggle. The frustration is dormant and will remain inactive.

The village has some 30 hand pumps, each shared by a cluster of households, about three families on an average. But they have been installed on flat ground without considering the floodwaters that submerge the land, including the hand pumps every year. So is the case of latrines – all built under the central scheme, Swachh Bharat Mission, ignored all guidelines and designs for flood prone areas; both hand pumps and toilets need to be designed on an elevated platform, several feet higher than the observed flood water level. Naturally, these sanitation facilities, popularly referred to as ‘Modi latrines’, do not work when they go deep under the flood waters, exposing all human excreta.

Inevitably, water-borne diseases like diarrhea and jaundice break out. Usually, when the Ranganadi, Subansiri, and Brahmaputra are in spate, many floodplains get inundated, destroying crops and livestock, and displacing thousands of families from their homes. The network of embankments also hampers the natural drainage of floodwater. The excess water fails to recede to the river and remains stagnated within the village premises, especially on the land next to the embankment; all these places then become the breeding sites of mosquito that spread malaria in the nearby villages. Diseases are common in cattle or livestock too.

Life & Livelihood – living with uncertainty

The flood not only leaves a trail of devastation but also creates a new landscape with massive siltation or sand casting of farmlands on the one hand, and loss of fertile arable lands to erosion, on the other. These factors, along with other climate uncertainties, push the agro-based rural economy to a precarious situation. Villagers talked about a host of climate-related factors that determine the outcome of agriculture. A favourable climate with regular rainfall helps timely farmland preparation in pace with the season; also, productivity and per capita share of the land used for cultivation all play a significant role. Suppose there are disruptions like a hailstorm in the flowering period of mustard (January). In that case, early torrential rain in the sowing period of wet-rice cultivation (March, April) or unexpected drought situations pose a severe threat to winter crops. Water logging in October does not allow the land to be ploughed and dried favorably.

Besides, sand-laden land requires years – at least six to eight – to regain its productivity. Ploughing earlier, at least three-four years before production, is necessary as it helps nourish the soil. The productive land faces the threat of erosion, patch by patch. All share the remaining land. The size of shared land continues to shrink because of the increase in the size of families. On top of all, there is the anxiety of flood and erosion-induced displacement, forcing people to find new land for settlement. With all these challenges, the youth have to look for livelihood elsewhere. Young people from Mudoibeel, like other surrounding villages, are always on the move to towns and cities in search of work and economic opportunities.

“We are peace loving people. When everything, maybe after 10 years from now, is lost, we will all shift to the other side of the river,” said Mithun Doley, a young man with noticeable leadership qualities. Well, that leads to another dimension, potential conflicts over control and ownership of land and water. Such disputes may not pop up within a given family but between different parties involved in commercial fishing and casual view over land rights while living in a designated reserved land. To have land rights, the community must settle in one given location for some period. However, their current settlement falls under the periphery of the Poba reserve forest, and in no way could they claim rights over land. As these settlement areas are within the boundary of the Poba reserved forest, and to date, there is no change in the status – that is, from reserved land to tribal belt or land with ‘periodic patta’. As such, none of the families has miadi (periodic) patta. Maybe, it is because of this uncertain status of their land, no proper socio-economic infrastructure – roads, drinking water supply, and irrigation facilities, etc. – has come up in these places. After all, how long could they rely on rainfall to cultivate cash crops? How long could they drink river water?

The bend of the river is ever approaching the heart of their village. As erosion and the fear of losing home are so profoundly rooted in their minds, no one cares about the importance of safe drinking water. No one cares that their water has not been tested and treated. On the other side of the river, over the horizon tall grass, buffaloes, cranes, and ruddy shelducks – all sharing the same landscape – the sun is setting, spraying the remaining spectrum of colours. Maybe 10 or 20 years from now, that space will be occupied by these land lost people.

Post Script: It’s been several months now since the water talk took place. In between these months, that bend, where we stood for a photo, changed its contour. The river ate up more than 1.3 km and moved close to the Karak tree that still stands proudly in the middle of Mudoibeel village.

(The visiting team included: Manas Jyoti Chutia, Dharani Payeng, Rebat Baruah, K.K. Chatradhara and Monoj Gogoi)

About the writers:

K K (Keshoba Krishna) Chatradhara, popularly known as Bhai, born in the 1980s in Subansiri valley, is an eminent river activist, writer and social researcher looking after the rivers, dams, and water in Northeast India. He likes to introduce himself as an environmental survivor who lives in the Subansiri valley of Upper Assam. After completing his Master in Computer Science, he went back to his native land to work for his community and started the environmental movement in Subansiri valley. (kkchatradhara@gmail.com, +91 94354 91437)

Manas J. Chutia has worked in various capacities with different organisations ranging from education to development. He has been a freelance content writer. His area of interest is primarily in literature, culture and society. He is also a photo enthusiast and has volunteered for photo documentation on natural heritage and people. He is one of the key persons in developing water narratives. (manasjyoti30@gmail.com, +91 99545 07104)

Geolocation is 27.064327826140893, 94.14034408248683