|

"Only an additional embankment can secure this place properly We are glad that the new representative and the village body has taken up the issue Some grant of eleven crores have been sanctioned for the new project It will perhaps materialize once the flood season goes We are optimist about it"

"When this existing mathauri embankment tore off a lot of people came to see what has happened As this is the shortest road route from LengaKuruwa and it broke just here in Lenga transportation to Kuruwa halted for weeks Few of us took our canoes to ferry a few needy passengers to cross the breach and head to North Guwahati They had important things to do"

"We will come up for the proper repairment once the Raax festival is over This is the first time our village is independently organizing one We are really excited"

K Deka a resident of Bhati Kuruwa Darrang

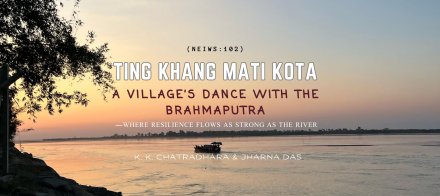

Kuruwa is a riparian village on the south-western flanks of Darrang, a district that amasses a substantive area and terrain in northern-bank of middle Assam. Though it has been a part of the Mangaldoi sub-division, its riparian location puts it on the peripheries of the district administrative jurisdiction, with the Brahmaputra River and its sediment-laden deposits i.e. the chapori being its immediate neighbours. The shortest route that links Kuruwa to North Guwahati – the node from which ferries ply to Guwahati frequently – is the Rangamati-Kuruwa embankment-cum-road that extends for more than twelve kilometers. Being the shortest in distance and being linked to different portions of the rural hinterland through unmetalled arteries, it is the route that most village passengers and commuters prefer.

However, there is another signifcant reason why this particular route witnesses more footfall. Only one ferry-vessel which is registered with the Inland Water Department (IWT) of Assam plies directly from Kuruwa to Guwahati, across the Brahmaputra river. And that too, only once in a day. Departing from Kuruwa at nine in the morning, the ferry arrives back from Guwahati at five in the evening. Given this narrow window to access the only possible waterway, most travelers and commuters who couldn’t make in time are left to undertake the roadway, i.e. through the embankment. This makes the Lenga-Kuruwa embankment road dear for many, and especially for the professional menfolk with motorcycles and bikes.

In the July of 2022, this very embankment-cum-road tore off one fine morning. Deluge water overburdening the paddy fields that the very embankment was supposed to protect rammed the lumped dyke. The deluge was a result of a heavy downpour as well the overflowing of the Nanoi river that traverses through the Darrang region from the foothills of Bhutan. The impact of this came tumbling on the downstream and riparian fronts of Darrang, and Kuruwa being its worst-hit victim. The water evidently pushed through, making its way through the slanting terrain of the paddy fields and finally discharged itself to the valley’s most prominent drainage system, i.e. the river Brahmaputra itself.

Technically, the floodplain was engineered in a manner that certain paths were carved to channel excess water in times of deluge. Two sluicegates were constructed in the area – to dictate water in times of flood to follow the trail of the tributary Bornodi and make its way to Brahmaputra. Unfortunately, being uninitiated in the disciplinary arithmetic of science, the flood seldom followed such precision. Water thrashed and the embankment was breached. Or to put it more poetically, it is where the water found its way.

(The Rongamati-Kuruwa embankment-cum-road, the portion in Lenga where it tore off.)

(The zone of breach – after it was mended. The structure is supported by cane and wood.)

The floodwater, as a local contractor told me, was very unruly this time. asked further if floods were ever obedient to human sentiment and the economy of engineering. His response smirked of denial. He subtly putt forwarded that in general, embankments have been successful in securing land from advancing waters. On asking more about how the breach occurred, Rudraneel Barua, a teacher in the village government school narrated an explanation.

‘The water overrode. The sluicegates were compromised. Moreover, there is one more dimension to it. In this place, where the water tore the embankment, there used to be a fishery of a local club called Luitporia Yuva Sangha on the outer side. The mahaldar who was in charge of the fishery emptied it just a few weeks before. There were a lot of ui, i.e. white ants or termites that pestered the fishery. Hence, there was also a pressure asymmetry in terms of approaching water on one side and vacated water on the other. A few big trees were also uprooted. The deluge therefore, rushed through this site – tearing off the embankment for a hundred meters at least.’

(On the right is the fishery that was vacated, and further away is the Brahmaputra.)

The causality was immense, as many affected locals informed. All agrarian land and households south of the NH 15 in Dumunichoki were inundated. It was also at a time when the farmers were ready with saplings of wet rice paddy to be transplanted in their fields. Nothing was spared. For most of the working-class people who commutes to Guwahati or elsewhere, it was the road breach that affected them the most.

However, the story of the embankment breach takes a fresh turn once the water recedes.

‘The mending of the embankment was a bigger challenge. We needed assistance from the Government and a lot of money and material. We couldn’t do it alone with the resources at hand.’ (K. Deka, a local resident)

Following up with a few more locals, I came to know that there was a confusion regarding which particular government department would monitor and assist in the repairing of the embankment. As the embankment initially was constructed by the Water Resource Department and the road therein by the Public Works Department, a confusion floated amongst the local contractors concerning to which department they would direct their quotations to.

This confusion, I pondered, reflects the ambiguity that underlines the logic of governmentability and the grammar of administration in terms of ‘managing’ ecology and its many moods in the region. My exposure to certain literature on sociology, politics and history of human-nature interactions in South Asian fluvial and ecological spaces kept me reminding the inherent contradictions that most engineering and technocratic interventions have had in the region. Of course, the history of the Water Resource Department in Assam traces its genesis to the concern of protecting cadastral villages from what many colonial ethnographers and officers termed as ‘evil floods.’ Juxtaposing my reading of such literature with what I experienced in the field in Kuruwa, I am more perplexed with the manner in which such age-old ad-hoc interventions, which were underscored by the imperial logic of accruing revenue and fortifying land to facilitate a constant flow to the imperial treasury, have naturalized in the contemporary period. Moreover, these colonial engineering relics have also received legitimation in the post-colonial period – spearheaded by the state firmly and in an ambiguous parlance by the affected population themselves – enforcing and lingering the straightjackets of colonial governmentability in a nobler fashion.

The promise of engineering and infrastructure in today’s world is definitely enchanting. The aspirational element of capitalism has given a newer life to the naturalization of certain inherited colonial interventions. Studying natural calamities like that of flood and its many moods, therefore, make these complex historical and political undercurrents pronounce and profound. On a personal note, Kuruwa happens to be my maternal ancestral place of origin and certainly, due to anthropological vanity, I tried not to bring this at the very beginning of this note. Thus, needless to say, the plight was personal. The sun was setting on the horizon and the waters of the Brahmaputra was turning crimson in colour. The daylight slowly faded as I made my retreat.

[1] The author is a postgraduate student of Political Science at Ramjas College, University of Delhi. He can be reached at kalitaunmilan20@gmail.com

Geolocation is 26.016516590876883, 91.4784364