|

“Water is life!” This oft-repeated statement may sound like a cliché but water is an inalienable part of human existence; not only just humans alone – almost all living creatures, the flora and fauna, depend on water for their survival. There is a popular Assamese pravasana (proverb) that says,”Sang lo Sang lo Ghyatir Sang lo; kul lo kul lo nadir kul lo!” (which means, for a secure good life, one should always try to maintain relations with relatives; and settle down the river side).

In the past, the native Assamese population was fully aware of this folk knowledge and accordingly adopted a riverine culture. Even the Ahoms followed the same mode of lifestyle. Securing water was one of the key activities of the Ahom period, and the inhabitants – from the royalty to nobility and to the ordinary people – carefully harnessed the river water for various purposes. Not only that, the Ahom kings constructed different kinds of water harvesting structures for conservation and effective utilisation of water. Digging ponds of all sizes, small and large, was one of the specialties of the Ahom period.

For example, when any family plans to build a new house, it will first dig a trench all around the property, and will also dig a pond in a suitable part of the residence. All this dug soil from the trench and pond will be used to prepare the ground floor of the new house and level up its courtyard. Beside the household pond, the Ahoms also would construct community ponds to ensure access to safe drinking water for all. However, the sites for those community tanks were selected after a thorough survey and scientific study of the aquifers so that water was available throughout the year and safe for human consumption. In fact, the Ahom kings used to depute certain ranked officials, especially the Barbaruas, to oversee all pond construction activities. Ponds served multiple purposes, such as:

-

Access to safe drinking water all the time.

-

Fish production.

-

To provide irrigation to the adjoining lands.

-

Get water in time to soak the Kothia (twigs).

-

To commemorate a king, a queen or a royal officer.

-

Construction of fort around Rajkareng, digging of khawai etc. for defence.

Rules for construction of Ponds

Elaborate rules were observed in matters of construction of water structures, particularly the ponds, because of their strategic importance. The Barabaruas were mainly responsible for carrying out these works. In addition to the ponds, they were also tasked with the construction of fort, daul, wall, etc. The paikes were engaged to dig ponds. Other subordinate ranked officials – Hazarika, Saikia and Bora – were also consulted before any digging activities were undertaken within the respective jurisdiction of the Barbaruas. Also, in extraordinary situations, Mohan Deodhai pundits, who, local people believed, possessed some magical powers, were invited to identify water-bearing areas by using Bancheng (a sort of sorcery).

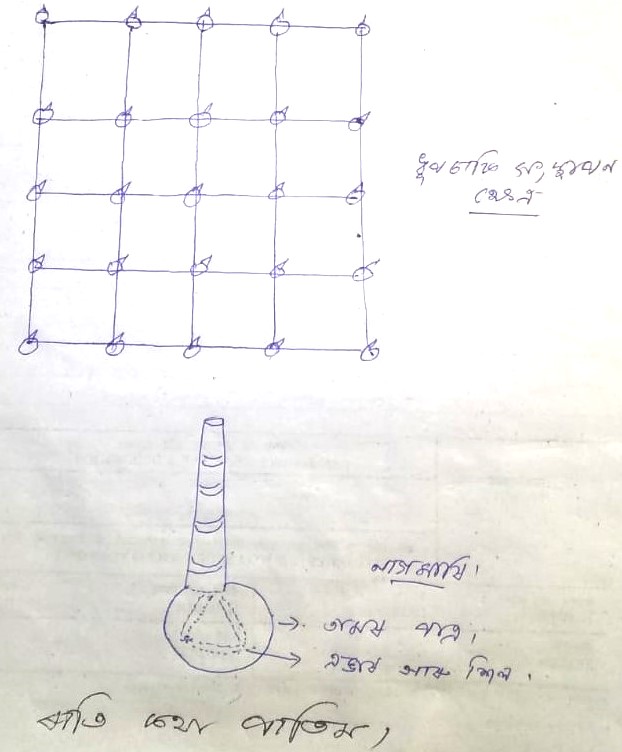

The pundits would employ a unique technique to find the source of water in a particular area. They would draw a huge square on the ground of a proposed site. The entire demarcated area would again be divided into 16 equal square parts. Then a total of 20 wooden poles would be erected in the four corners of the large square and inside one each of its 16 squares; a mustard oil lamp would be lit and placed on the top of each pole. They would keep a keen watch on the burning lamps on the poles, and track that flaming lamp, which got snuffed out first in the wind. That pole position would be considered the centrepoint of the proposed pond. This method is usually used while constructing the huge water bodies to regulate the force of strong waves created by high winds in the middle of the large pond. It was said that the waves generally would weaken when they reached the shores of the tank, and thus, prevented possible erosion around the pond. Apart from this, temples (devalayas) and daul were also built on the banks of such large water tanks so that people regard those areas as sacred, and do not pollute the water.

According to another source, someone would hold a burning mustard oil lamp placed in a specially built carrier and take a brisk walk around the proposed construction site of the pond. Wherever the flame of the oil lamp would go off that point would be taken as the centre of the water body, and accordingly, the digging would continue until the entire pond was completed.

Once digging is done, the next step is to purify the water body. And for that, a large copper plate is placed in the middle of the pond at its bottom. (It is said, drinking water in a copper container is beneficial for health). Some mercury (rah/ para/parad) is poured into the plate and a pole is fixed on it. In addition to rah, some gravel stones and lumps of charcoal were also placed around the pole (nagmari) to cleanse the water body. Interestingly, this rah was extracted from the bel leaves. And as rah is applied in the water body, some ponds are named as rahdhala, Rahkhowa, etc. Another significant aspect of these ponds was that water level remained almost intact in all seasons. Till today a few of such ponds constructed during the Ahom period exist in some parts of upper Assam. A nagmari can be seen in the Hatigarh pond near Jorhat even now. It is believed that nagamari is named after Nag or Nagini, which emerged from Agni (fire), the celestial god of energy. The nagmari is made of a wooden pole with an iron plate fixed on its top.

During my childhood, I heard a short story from my mother. It was like this: Once there was a severe drought in Assam; it didn’t rain for weeks and months. All crops in farmers’ fields got dried and perished under the scorching sun. People performed all kinds of folk rituals like arranging weddings of frogs (vekuli) to propitiate the rain god and ask for his blessings. But nothing worked. Thousands of people in desperation started to dig the earth everywhere in search of water; digging continued for days and nights till they reached from one end to another end of the earth. Suddenly, they heard violent shouts of other people from the depth of the earth; they were apprehensive of an imminent conflict with the other people. So, they decided to pull back and return home.

The story (sadhu) talks about the acute drought and digging of large ponds and canals by drought-hit populations in their desperate search for water, but there is no written history that suggests any such calamities in Assam. One may marvel at the sea-like water bodies of Jayasagar, Sivasagar, Rajmao ponds in upper Assam, and the fact that people are still using water from these ponds for the last hundreds of years!

Why were these huge ponds and water bodies created? Did Assam face frequent droughts in the past? There seems to be no written history about this, except people’s stories like the one my mother told me.

_______________

About the writer:

Girin Chetia is a director at North-East Affected Area Development Society (NEADS). He started his career as head to promote rural finance in National Institute of Bank Management from 1976 to 1979. Later he worked as field associate and training in charge at People’s Institute for Development and Training (PIDT), New Delhi from 1979 to 1990, associate and programme officer of Oxfam India Trust from 1992 to 1996 and as consultant from 1996 to 1998 (Kalkata Regional office). He is a contributor to an important training handbook on development in Assamese language named “Prashikshak Prakhikhyanor Hathputhi”. He is also the author of “Sakriya Setonar Anusondhanot” – a book in Assamese language on conscientisation. He is one of the pioneers of developing the social sector in Northeast India. Also associated with North-East Water Talk, Girin Chetia is the person who started educating people on water resources during the 1980s, when there was very less sense of water scarcity in Assam. (girin_neads@yahoo.co.in, +91 99544 51278)